Earthworms, Volcanoes, and What it Means to be a Scientist

Teachers are often asked the following question, "What makes someone a scientist?" Students in all grades ask this question a lot. Although there is no one clean answer, we hope to provide a little clarity for our teacher friends out there.

Being a scientist means being curious, passionate, and resourceful. Being a scientist means using evidence to make claims. It's a way of thinking. It's a mindset, but where does this scientific mindset come from? Is there a special combination of internal ingredients necessary for one to develop a scientific mindset?

To answer some of these questions, we will focus fire on the impact curricular resources can have on the development of a scientific mindset. These resources have a unique ability to influence the teaching and learning of science for every teacher, student, and parent in an educational system.

The messages and stories found in science curricula can make a profound difference in how students think about and approach science. If there is an emphasis in the curriculum on the who, what, where, when, and why underlining a scientific discovery, students' mindsets will follow. They might only value the outcome. They might only value the discovery, but what about the act of discovery?

The pattern in these curricular resources is familiar. We learn about a theory or concept, find out who discovered it, and are usually (and unnecessarily) provided with the year of their birth and death.

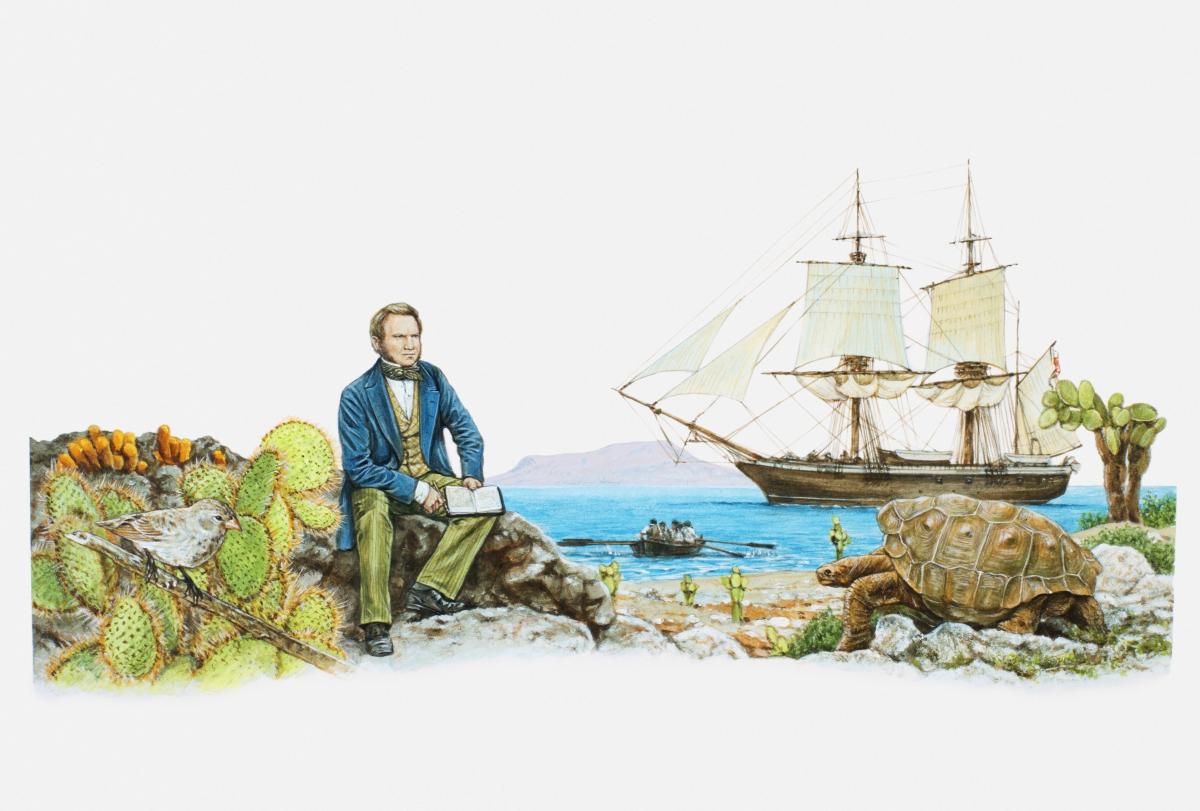

Dorling Kindersley/Thinkstock

Children are left to believe that these scientists had something very special at birth because virtually nothing important occurred between their birth and landmark discovery.

Take for example the theory of evolution. In many curricular resources, we learn about Charles Darwin, the famous scientist who was born in 1809 and how he developed the theory of evolution on the HMS Beagle. We are rarely provided with those intangible qualities and experiences that actually helped them develop their scientific mindset.

Did you know Darwin wanted to become a doctor but the surgical procedures made him sick? Did you know he also thought about becoming a priest but was more interested in the processes of the natural world? He was creative. He was a passionate tinkerer, thinker, and explorer. He loved asking questions and through his quest for understanding made some of the greatest scientific discoveries... ever. You might also be interested to find out that for over 40 years, he studied earthworms.

That's right, earthworms.

Ben185/iStock/Thinkstock

In the mid-1800s, most earthworms were considered pests, but Darwin thought there was more to their story. He was interested in a certain species of earthworms and their distinctive ability to take soil from below and poop it out on the surface. He thought there must be some benefits to this recycling and wanted to know more about what made them do this.

Darwin asked questions about earthworm behavior, their eating habits, and (even though he knew they had no ears) how they responded to sounds. He was meticulous in his research. He placed different pieces of food in front of the earthworms and recorded the results. He discovered that most earthworms liked eating carrots and preferred raw fat to raw meat.

He measured how much soil each worm could deposit in a single trip to the surface, estimated how many lived in each acre of English soil (roughly 54,000 if you are interested), and then extrapolated that worms recycled over ten tons of soil per acre each year! He found out that even though they didn't respond to the sound of a metal whistle, or the blaring sound emanating from his son's bassoon, they did respond to the vibrations from the top of a piano.

The amazing thing we learn about Darwin from these stories and peculiar images is that he was steadfast in his desire to answer his own questions. Darwin the scientist was made because he was curious about the natural world, asked questions, and sought out his own answers.

Darwin is a well-known story of discovery and triumph. We would like veer off the beaten path and share an interview with an unknown, up-and-coming scientist. By sharing her experiences as a kindergarten student and talking about her current research interests as a doctoral student, we get a glimpse of how her scientific mindset developed over time.

Like many others out there, she is asking her own questions and seeking her own answers. We'd like to introduce the talented Arianna Soldati, a PhD Candidate in Volcanology (one who studies volcanoes) at the University of Missouri--Columbia.

Photo by Dr. Alan Whittington

Hello Arianna, thank you for making the time. What was your earliest memory as a child (as it relates to science)?

When I was in kindergarten, Mt. Pinatubo--a volcano in the Philippines--had a big eruption. I saw footage on the news, and it made such a big impression on me that I didn't talk about anything else for days. It has stayed with me since.

What was your favorite class in elementary school? Why?

Science of course! Curiosity has always been one of my main traits, and once I discovered that science could help me find the answer to my questions, I fell in love with it. It was a perfect fit really; it still is.

Who was your favorite teacher growing up?

Professor Leopardi, my middle school science teacher. He prompted us to ask "why?" all the time and guided us in finding our own answers. He didn't just teach us science fundamentals, he taught us what it takes to make science: an inquisitive mind and spirit of observation.

What motivated you to pursue a career as a volcanologist?

I am interested in so many things, but I could only pick one career, and that was a big challenge for me. In the end I figured that my lifelong fascination with volcanoes was my best shot at staying excited about my job for a lifetime. I felt safe choosing volcanology as a career. And when I first saw a volcanic eruption live (Stromboli, Italy) during a field trip in my 3rd year of BS, I just knew I had made the right choice. Besides, the job has some amazing perks. You get to travel the world, and in a very special way. You are allowed--expected!--to go places tourists can't. When a volcano creates new land by emitting a lava flow, the very first people that get to walk on it are volcanologists, how exciting is that? You see amazing things in the field, and when you get back to the lab you get to figure out how they happened. I can't think of a better career.

Who have been your role models? What do you find most fascinating about their work?

All of my advisors have been great role models. I am intrigued by their ability to investigate very different volcanic processes, re-starting the processes to learn about them to the point of becoming experts and then pushing the knowledge boundary a little bit further each time.

What characteristics do you respect most from your role models?

I respect their work ethics, perseverance, and intuition.

What are your specific research interests?

I focus on lava flow rheology. I am interested in understanding how lava behaves as it flows away from its source vent. This is quite challenging because lava is made by molten rock, crystals, and bubbles which makes it move in quite a different way from let's say pure water.

What question(s) are you hoping to eventually answer?

One of the cool things about volcanology is that it is a very young science, so there is a lot that we don't understand yet. I hope to eventually discover what triggers effusive eruptions and what controls what happens after the lava is out of the vent (i.e., how far will it flow, in which direction, how fast...)?

Do you have any volcano-related trips scheduled for the future?

I do! I'll be traveling to La Réunion in the spring (an island in the Indian Ocean off the cost of Madagascar, which is a French oversea territory) working on the very active volcano (four eruptions since the beginning of the year!) Piton de la Fournaise.

Thank you so much for your time.

Let's go back to our original question, "What makes someone a scientist?" I believe having a scientific mindset makes someone a scientist, and a new one is produced each time someone asks a question. Sometimes these questions are complex, like Arianna's pursuit to understand lava behavior or Darwin's quest to understand the impact earthworms have on society. Other times these questions are subtle and sweet, like when my two-year-old daughter Evie, pictured below, asked me where sand comes from and started digging a hole, presumably seeking the answer. In each example, a phenomenon was identified, a question arose, and an answer was sought. In each example, these scientists were

- curious,

- passionate,

- resourceful,

- and realized science was more than a class we take in school.

It's a mindset. It's a way of thinking, which means anyone with a question can be a scientist.

Image by Brian Mandell