Whenever I'm engaged in small talk at a conference, soiree, or any other miscellaneous function where people talk about what they do (in Washington DC, that happens to be all functions, everywhere), someone invariably responds to my description of my vitae with a well-meaning, "It's so great that you are showing kids that science can be fun!" Of course I appreciate people's enthusiasm in what I do; I firmly believe that science education is the most interesting thing a person can do.

Watch this video. WATCH. IT. If you're anything like me, it will leave you with your mouth hanging open, slightly unsettled, at one of nature's most incredible, disconcerting, skin-crawling species:

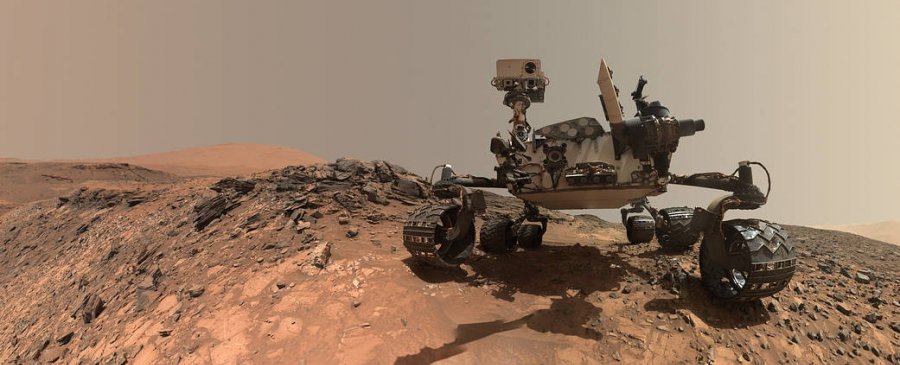

At 140 million miles from Earth, Mars isn't exactly a stone's throw away -- in fact, it takes about nine months (and several billion dollars) to reach the Red Planet via rocket. Although rovers and satellites can teach us a lot, scientist have found a cheaper, more convenient place to study Mars: the Earth.

If you have ever closely studied members of the phylum Echinodermata, you might ponder, "How can I tell a male sea cucumber from a female?" In this case, you would be prudent to accept the wisdom of accomplished scientist of echinoderms Dr. David Pawson who implores, "First you must ask its name." Humorous bits such as this were woven into a week of intensive science exploration that took place at the SSEC's 2015 Biodiversity SSEAT.

"Here's the deal, Jack. Children need to find ways to make sense of the world around them -- we all do." --Gummerson

If you've seen Good Thinking!, SSEC's new web series on "the science of teaching science", you've probably seen Gummerson -- and perhaps wondered who (or what), exactly, he is?

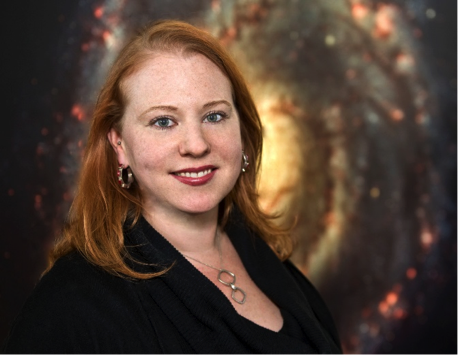

Dr. Jennifer Stern is a Space Scientist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Katya Vines, a Science Curriculum Developer at the Smithsonian Science Education Center, recently interviewed Jen about her role on the Mars Curiosity Rover team and her path to becoming a space scientist. Some of Jen's answers may surprise you!

What was your favorite class in school?

On America's first Fourth of July celebration in 1777, fireworks were one color: orange. There were no elaborate sparkles, no red, white, and blue stars -- nothing more than a few glorified (although uplifting) explosions in the sky.

As it turns out, although we've been lighting fireworks for the last 2000 years or so, modern fireworks were only invented in the 1830s -- so, what were they like before then? When Henry VII had fireworks at his wedding in 1486, how did they look? How have fireworks and the science behind them evolved throughout history?