Prepare for Disaster

I have a friend from when I lived in Ohio. We dealt with lots of lake effect snow and the occasional blizzard warning. She moved to Seattle and she experienced lots of rain. Then she moved to Charleston just before Hurricane Matthew hit in 2016. About a year ago, she moved to southern California. Last week I received a text from her. "I do not like earthquakes."

Melissa Rogers

Melissa Rogers

On 5 July 2019, a magnitude 7.1 earthquake occurred in Searles Valley, California. As of July 11, 484 earthquakes that were strong enough to be felt and five earthquakes that were large enough to do damage occurred in the area. There is nothing particularly unusual about this sequence of earthquakes. And perhaps that is what makes this such an important reminder of two things.

Colored lines show limits of different amounts of shaking. [USGS Interactive Map] Mainshock, USGS Shakemap

Colored lines show limits of different amounts of shaking. [USGS Interactive Map] Mainshock, USGS Shakemap

- Natural hazards are only hazards when they impact humans. In the general scheme of things, they are just natural events. This is true of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, landslides, floods, and any other event we hear about on the news.

- Because such events happen regularly on Earth, the best way for humans to keep an event from being hazardous is to prepare.

How does one prepare? The website Ready.gov is a great place to start. Their two major suggestions are Be Informed and Plan Ahead. Here’s a summary of information from this site and several others.

Become familiar with natural events that could occur where you live or in an area you plan to visit. If you are new to an area, you may want to start by asking your neighbors. They may also be able to share information about community alert and support networks. You can look for maps showing flood-prone areas and earthquake hazard maps through Federal Emergency Management Agency sites.

Make a plan.

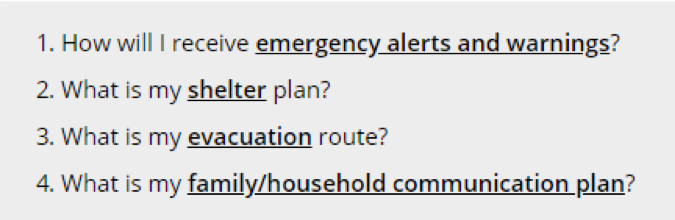

Ready.gov suggests starting a plan with these four questions. Ready.gov

Ready.gov suggests starting a plan with these four questions. Ready.gov

Learn about ways to safeguard your belongings. If you live in an area susceptible to flooding, use watertight storage containers where possible. To limit damage due to earthquake shaking, secure furniture to building structures and small items to shelves.

Prepare a response kit. This could be something to grab in an evacuation or it could be supplies to use on site following an event. The Earthquake Country Alliance has some good suggestions.

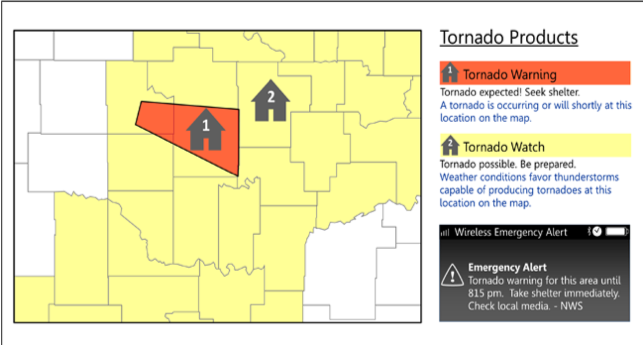

How will you receive warnings? What types of warnings will be issued if an event is forecast or is happening? If it is forecast, what should you do and how much time do you have to act? Hurricane warnings may provide you with several days to evacuate. Tornado warnings may give you a few minutes to take cover.

Learn what different warning statements mean. Weather.gov

Learn what different warning statements mean. Weather.gov

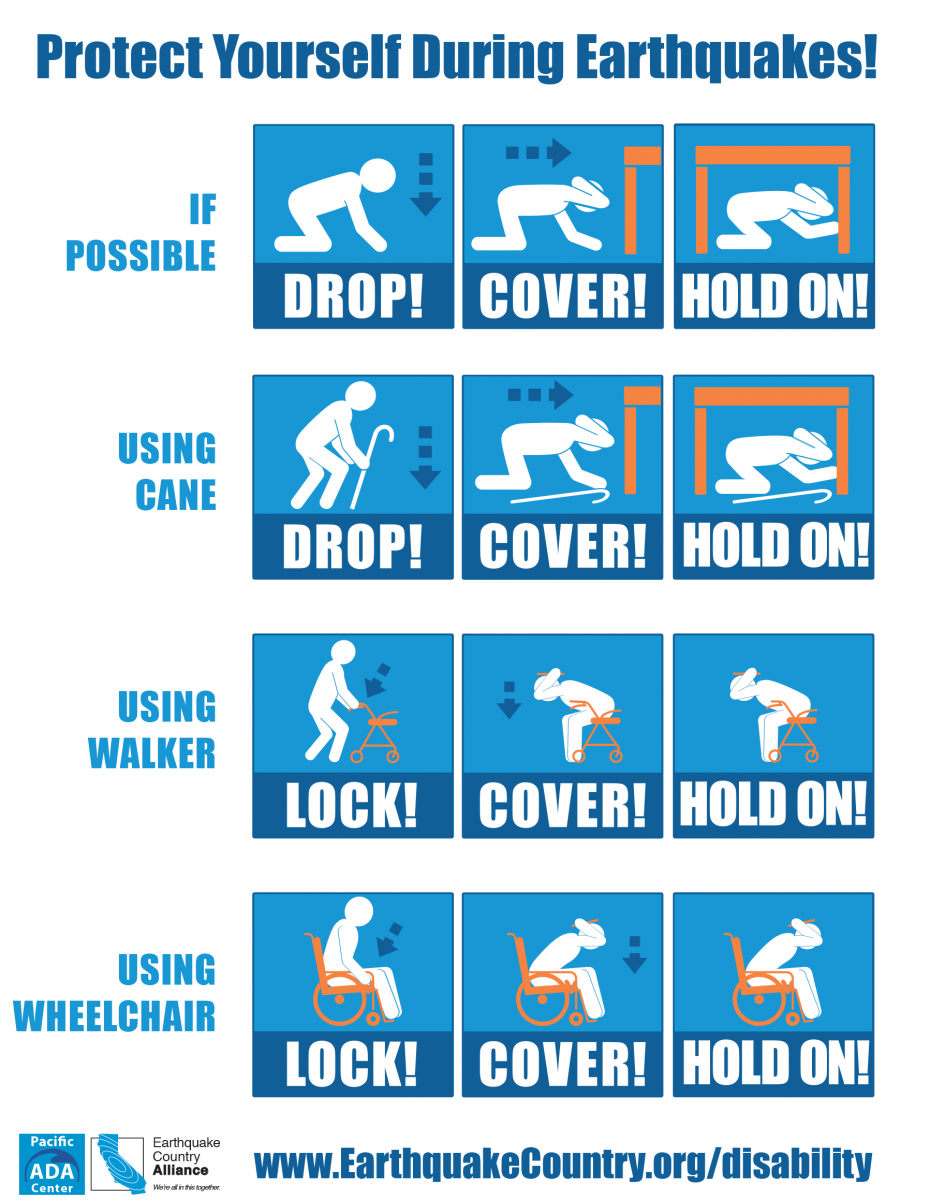

Many earthquake-prone regions now have alert systems that activate once an earthquake is detected. They can warn of specific levels of shaking with enough time for municipalities to stop trains, hospitals to safeguard operating rooms, and people to Drop! Cover! and Hold On! to protect themselves.

Courtesy: Earthquake Country Alliance

Courtesy: Earthquake Country Alliance

Prepare to be on your own. Depending on the nature of the event and the impact, you may be without electricity or water for days to weeks. This is where that response kit comes into play. But this isn’t only about having food and water. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have some guidance on how to deal with, well, poop after a disaster.

Interested in having students learn more about planning for and responding to natural disasters? Consider using the Smithsonian Science for the Classroom module called What Is Our Evidence That We Live on a Changing Earth? This module is designed for use in fourth-grade classrooms and includes lessons about where on Earth volcanic eruptions and earthquakes are common, features of earthquake-resistant buildings, hazards associated with tsunamis, and organizations that study and issue warnings for earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, and landslides.