A Triangulation Approach in Environmental Science Education

Written by Kristine Novero McCaslin

Engaging lesson plans, assessment questions, hands-on activities, and lab experiments. These are the key components I consider when planning science lessons. But as I have evolved as a science teacher, I realized that culture is also an integral component in helping us understand and connect to the world around us.

While studying in the Philippines, I joined an immersion program where our class visited the Mangyan Tribe in Mount Halcon. I leaned how they practiced “kaingin”, a slash-and-burn method in agriculture. I also gained an understanding of how they cultivated plants for medicine and the practice of food preservation. Fascinated by this experience, I wondered, “why haven’t I known about the Mangyan’s knowledge before and why is it not taught in schools?”

Now that I’m a teacher in the United States, I play a part in changing the narrative of science teaching. We can learn not only from the European scientific approach but also from other existing methodologies to understand and explore the natural world. I wanted to learn about the Piscataway and Anacostan Tribe because I live close to them now. But where to start? I found my answer through the Smithsonian.

Smithsonian Science Education Center (SSEC) and Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) publish educational resources showcasing cultures, identities and histories that give another depth to communicating science. I found a wealth of research-based classroom materials that focus on global sustainable goals from SSEC. NMAI, on the other hand, supports teachers with activities and lessons that incorporate key understandings of the knowledge, traditions and stories about Native American tribal nations providing educators more ways to know and present how the environment works. Together, resources from SSEC and NMAI are good starting points for teachers like me who aims for culturally responsive and relevant lessons. The materials are different, but both institutions complement each other making the navigation and integration easier for educators.

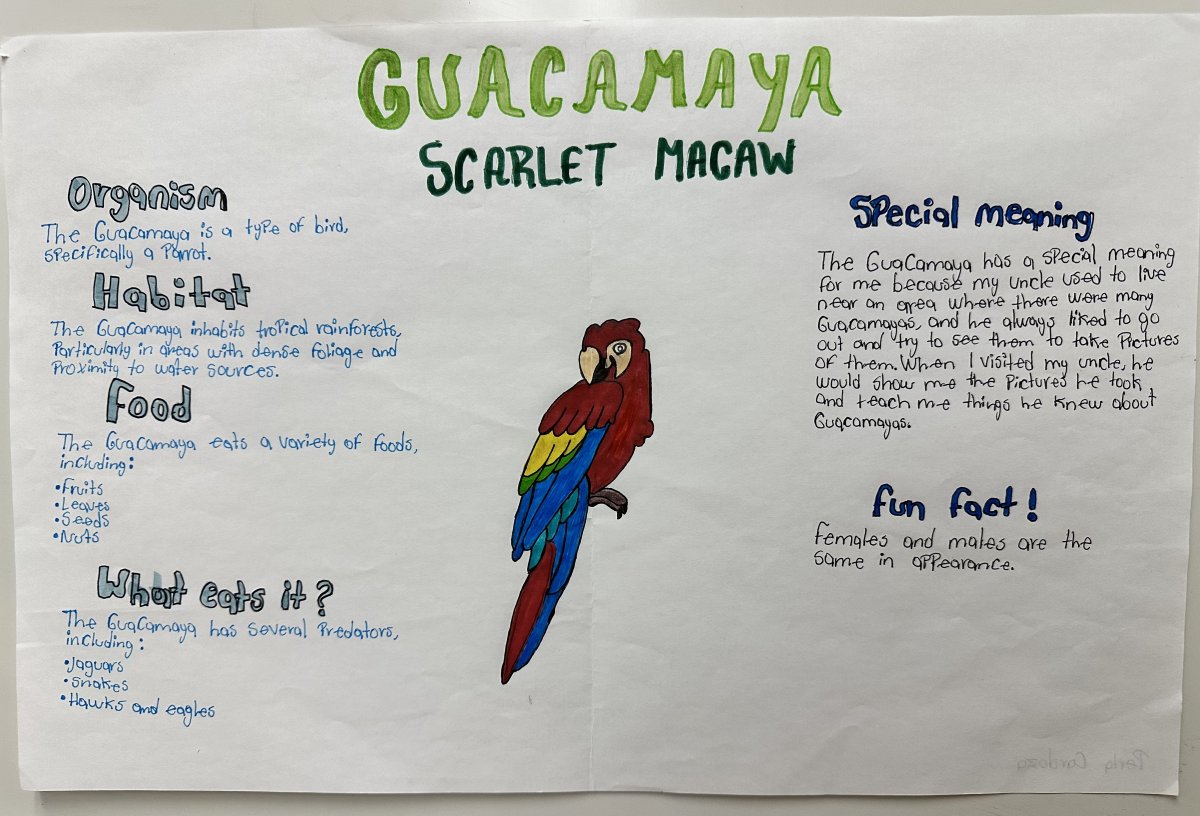

From SSEC, I learned the value of creating personal connections with science! I love the identity map from the Smithsonian Science for Global Goals guides. In my class, I started the biodiversity lesson with an identity map, followed by a poster-making activity where both scientific knowledge and cultural diversity were integrated. It was a proud moment for the students when cultural identities were represented while learning about science. We made connections! Students were highly engaged because they were heard and they were seen.

Then, I supplemented this activity with NMAI’s salmon game and stories of the importance of salmon to the Lumi Nation. It helped revisit a previous lesson about the water cycle and the Pamunkey Tribe’s Life Along the River story, also from NMAI. From there, we continued to study biodiversity, leading to energy flow, symbiosis, and ecological succession utilizing the Climate Resilience! guide from SSEC. This lesson circled back to how diverse yet similar we are, as demonstrated by the climate resilience stories told by people from different parts of the world.

Creating culturally relevant science lessons also gave me a broader perspective on my role as an educator. I don’t just state facts. I am also a storyteller of how knowledge is acquired. Knowledge comes not just from observations and experiments but also from experience and the handing down of traditions from one generation to another.

SSEC and NMAI are two institutions that give educators access and options in incorporating culture in science education. As an intern, I am also participating by giving them feedback on how their resources help teachers like me and suggestions for improvements. As I develop a culturally relevant classroom, I realize how this endeavor may lead to a larger scope, such as global classroom projects and professional learning communities. I know I will continue embarking on this journey with SSEC and NMAI, one lesson at a time.

About the Author

Kristine Novero McCaslin is the science department chair and a biology teacher in Thomas A. Edison High School. She is a doctoral student from The George Washington University under the Doctor of Education in Curriculum and Instruction program. Kristine is originally from the Philippines and now resides in Fairfax County in Virginia with her family, dogs, cats, turtles, and fishes.