Turning Frustration into Fame: How Dr. Jane Goodall Conquered Challenges in the Field

What words do you think of when you think of the name Dr. Jane Goodall? Chimpanzee researcher. Visionary scientist. United Nations Messenger for Peace. Expert. Leader.

How about failure? Maybe not.

But like every scientist before her and every scientist who will follow, Goodall encountered failure in the pursuit of science. All scientists fail. Einstein did. Marie Curie did. Your science teacher did. I definitely did.

This isn’t an insult, trust me. Goodall is one of the most accomplished animal behavior scientists in the world. She discovered that chimpanzees use tools, eat meat, and have complex social relationships. But those discoveries didn’t come without persistence and some measure of failure.

Failure is a normal, useful part of science. Failure knocks you down and dares you to try again with a better idea. And at the age of 26, during her first independent research project, Goodall did just that.

In 1960, Goodall was sent to Tanzania by Dr. Louis Leakey, a world-renowned anthropologist. Leakey asked her to study eastern chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) at Gombe National Park, a 52 square kilometer reserve on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in Tanzania.

The dense forest of Gombe National Park rises above Lake Tanganyika. Image: MattiaATH/iStock/Thinkstock

The dense forest of Gombe National Park rises above Lake Tanganyika. Image: MattiaATH/iStock/Thinkstock

Goodall arrived at the border of Gombe on the morning of July 14. She stared up at the steep mountains of the park, armed with only a high school education; a love of animals; and her mother, Vanne. She had just six months to achieve her objectives: find, observe, and record the behavior of the Gombe chimpanzees.

Things did not get off to a great start. Immediately after arriving at Gombe, Goodall, her porter named Rashidi Kikwale, and game scout named Adolf headed into the forest to find chimpanzees. Adolf noticed a ripe fruit tree that was likely to attract the animals. The team positioned themselves across from the tree, and soon a group of 16 chimpanzees appeared. Goodall was elated.

A pair of chimpanzees rests in a tree in Gombe National Park. Image: guenterguni/iStock/Thinkstock

A pair of chimpanzees rests in a tree in Gombe National Park. Image: guenterguni/iStock/Thinkstock

Unfortunately, the leaves of the tree prevented her from seeing any behaviors. Sometimes she’d spot a chimpanzee’s arm as it reached for fruit, but that was all. When Goodall tried to move closer to the tree, the chimpanzees fled.

Over the next eight weeks, Goodall and her team climbed up and down the valleys of Gombe, combing the area for chimpanzees. But they couldn’t find any other fruiting trees that might attract the primates. The undergrowth was incredibly thick and made for slow going. Streams coursed down the mountainsides, which hid the approach of Goodall’s team but prevented her from hearing the sounds of the chimpanzees.

In an effort to avoid scaring the chimpanzees, Goodall began observing groups from far across the valleys, almost 450 meters away. But the animals still fled as soon as they spotted her. And even when they didn’t run, they were so far away that Goodall couldn’t make meaningful observations.

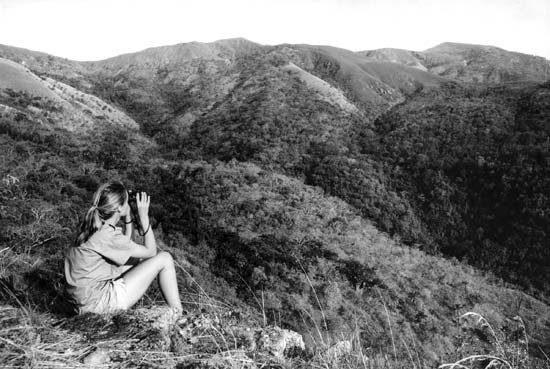

Goodall uses binoculars to view chimpanzees from a distance. Image: Baron Hugo van Lawick

Goodall uses binoculars to view chimpanzees from a distance. Image: Baron Hugo van Lawick

Goodall theorized that the size of her group was scaring the chimpanzees. She convinced Rashidi and Adolf to stay behind and tried approaching the groups on her own. The chimpanzees still fled.

It was an incredibly frustrating time. Some days Goodall saw chimpanzees for a few minutes. Other days she didn’t see a single chimpanzee. It did not matter whether Goodall was high, low, near, far, in groups, or alone. The chimpanzees kept running away.

Just when she thought things couldn’t get any worse, Goodall and her mother contracted malaria. High fevers, chills, and exhaustion kept them confined to their beds. She and Vanne survived the illness thanks to the care of the camp cook, Dominic.

Two weeks later, fighting back weakness, Goodall climbed to an open clearing high above the lake. Three months had passed with almost no data and only three months of funding remained. Something had to change.

Suddenly Goodall noticed movement about 75 meters away. Three chimpanzees had appeared across the valley. They turned and looked at her. Instead of fleeing, the animals calmly walked into the forest. A few hours later, a large group of chimpanzees began feeding on some fig trees at the bottom of the valley. The group stopped and stared at Goodall, but they did not run. She was able to observe the chimpanzees for several hours.

A chimpanzee in Gombe National Park. Image: guenterguni/iStock/Thinkstock

A chimpanzee in Gombe National Park. Image: guenterguni/iStock/Thinkstock

In her words, “It was by far the best day I had since my arrival at Gombe, and when I got back to camp that evening I was exhilarated, if exhausted…That day, in fact, marked the turning point in my study.”

Goodall’s experience illustrates that science is not a straight line from start to finish. It is an iterative process that requires a healthy dose of mental agility and perseverance. When Goodall reached a roadblock, she tried another method (and another, and another). So when your next experiment turns out to be a bust, don’t let it get you down. Failure is simply the price of admission in the scientific world. Welcome to the club!

Learn more about the process of science, the role of failure, and the value of persistence in Science: A Work in Progress and Attack the Knack, two Good Thinking! videos from the Smithsonian Science Education Center.

References

Goodall, Jane. In the Shadow of Man. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1971.

*Header image credit: Michael Nichols/National Geographic Creative